This book is available for preorder at: http://www.iitbombay.org/initiatives/hats/hostel4/madhouse-book-order

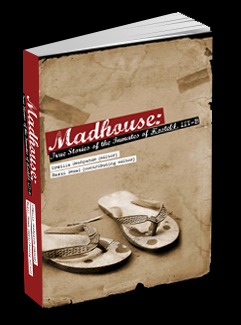

When my husband Ashish Khosla, once an inmate of Hostel 4 himself, told me a tale about one of his hostelmates going to lectures on a horse, I was not impressed. Though he is not given to flights of fancy, I thought he was perhaps making a lot of a single incident. Then he showed me the photograph. It had that unmistakable stamp of the early ‘80s in style and substance, and there was the white horse, and its rider, on their way to a lecture on organic chemistry. I realised that it was not a one-time event. I also commented then that it would be a fabulous book cover.

One thing led to another, and in March of 2010 I was given the privilege and frustrations of editing this book.

I have known IITans intimately through my life– my father, step-father, husband, boyfriends and many good friends. I made several good friends during the creation of this book. None of what I read and heard explains these guys, though. I still cannot tell whether they chose this gruelling and most prestigious of educational institutions because of the way they were, or they became that way because those five years they spent at IIT.

In spite of censorship (some language of course, and some entire incidents were left out due to the sheer indecency of the matter) it is quite clear that these boys – and they were boys then, indulged in very questionable behaviour. There was substance abuse, and it wasn’t the substances that were abused. There was people abuse – in fact abusing each other in picturesque and imaginative ways was a normal pastime. There was delinquency and there were criminal acts. Instincts of various nether levels were indulged endlessly and continuously. This book has chronicled many instances. It is my feeling that these memories are stronger than mundane ones of lectures attended or disciplines learned or even engineering degrees earned. In any case, these were more interesting to both listeners and narrators, and now, writers and readers.

There is something that I must make clear to the readers of this book. In spite of all the unsavoury behaviour, I must point out that these same rowdy and rude young men are now captains of industry, science and technology, some are prominent in the political and social arenas, and most are productive members of society. I say this as a reminder, because while reading about their early lives in their own words, a reader might, understandably too, forget this fact.

It is my feeling that in safe and tranquil IIT Bombay, these young men felt free to experiment physically and intellectually. The feeling of safety came from having made it into IIT – not an easy task. All they had to do now was make it through the next five years, and life after that could only be easy. They were far from the rules and conditioning of their homes, thrown together with some like and some utterly unlike themselves. They had unbound and yet protected freedom that allowed them to find themselves. And they looked hard, and pushed themselves and their mates over and under and any which way they could beyond known boundaries.

I think such investigations, that might be thought of as foolhardy at best and immoral at worst, informed their morality. These men left IIT with a degree, and also with a self-made morality. Like the degree, that morality, though not conferred, resulted from a process. It involved hypothesis, argument, experiment, and conclusion. It is more personal, and more solid than the societal rules and regulations that pass as moral code.

As a project this one was interesting to me in another way. Here was a large number of stories coming to me as they were remembered. One or two or three of the guys are good writers, and I had no trouble with their pieces, other than chopping down some unnecessarily verbose bits, or changing the sequence of the narration to make it more appealing to a reader, moving the twist to the end, emphasizing foreshadowing, deepening suspense. But some of these guys are not writers. They simply put down in words their memory and feeling about an incident with a few relevant and irrelevant details, and sent it off to me. These are the ones who taught me something about writing. In the beginning I would think, this story has meat, if only I write it in my own words. So I re-told the story, in my own “better” words. And every time I did that, I found that the whole feeling and content changed. I learned firsthand something I had struggled to understand for a long time – something I knew to be true in theory, but didn’t understand until this project: that style and content are inseparable. That by adjusting Raj Laad’s piece to make it sound more like me, I was in fact losing the voice of Raj Laad, of course, but also his perspective. And it was his perspective, in his words, which was the content of the piece – not the sequence of events . And I promised myself I would not convert all these pieces to fit an acceptable grammatical or linguistic correctness, and I would not make the stories into a homogenous list of rude and crude incidents in the lives of teenage boys from a certain hostel. I hope I achieved this.

(Excerpt: My introduction in the book.)