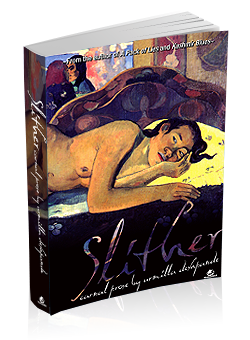

Slither ~ carnal prose

Witches, kings, goblins and hawks live in these pages alongside painters, mothers and taxidermists.

In her third book Urmilla Deshpande writes the erotic, the obscene, and the intimate in eighteen tales of graphic carnality and delicate longing.

Review

By Roselyn D’Mello

… Contrary to popular belief, a thick barrier lined with barbed wire separates erotica from pornography. If ‘pornography is the attempt to insult sex,’ as D H Lawrence suggested in his essay ‘On Pornography’, erotica is the attempt to celebrate its roots – desire. The two genres are motivated by entirely different impulses, but it is the degree to which the act of sex is alluded that demarcates the boundaries… to write a single line of erotica from scratch, you must first create the universe.

That is precisely what Urmilla Deshpande seems to have done in Slither, her collection of erotic stories published by Tranquebar. The cover defines this body of work as ‘carnal prose’, and with every story a new dimension of this secret universe of flesh and fire unravels. The atmosphere is dense with alternating layers of desire and desperation: a single fertile river that runs underground and bifurcates into diverse streams of consciousness, infusing and irrigating everything it encompasses with passion and intrigue. The landscape is peopled with characters who live ordinary lives and who dabble routinely with the mundane, but who experience the world in all its sensual glory. But Deshpande’s true genius lies in her ability to play with the texture of language, to ‘spank words carefully’ and to create a dialogue between touch and the sensation of that touch – and, often, the longing for it. And finally, her capacity to linger in the afterglow of language so that what arouses the reader is not merely the quirkiness of the situation at hand but the symphony that her words conduct.

…The 18 stories spread over nearly 300 pages embody a range of characters who are, more often than not, of Indian descent, though not always located in India. Among the most notable we have the botanist’s wife, who finds herself seduced by a village chief in a village along the foothills of the Himalaya; an emotionally unavailable taxidermist who finds herself attracted to another emotionally unavailable person; a member of a family of spirits who can enter and control people’s bodies, a village girl who grows up to be an internationally acclaimed swimmer and who is desperate to lose her virginity and finally does so – at 50.

‘Goblin Market,’ Deshpande’s retelling of the eponymous poem by Christina Rosetti, is easily the most subversive. Here, the two sisters Lizzie and Laura are lovers, and the goblins in question are ravaging beasts with the power to corrupt one’s innocence.

… ‘Isis’ and ‘Slight Return’ are the two other strongest stories. In ‘Isis’, the narrator, a young writer, gets increasingly obsessed with the title character, a yesteryears actress whom he would keep hearing about through his grandfather, who always speaks of her lustfully. He decides to write a book based on her and finally meets this almost mythical figure, finding himself further intrigued by her grace, her beauty and her missing eye. ‘Slight Return’ is a heartbreakingly beautiful story about Suman, a middle-aged woman and victim of a bad marriage, who finds herself transfixed as she chances upon her daughter clandestinely making love to her boyfriend in the dark. Her reaction is not one of horror or shame; instead, given her own negative sexual history and her experience with rape victims and prostitutes, she finds herself strangely appreciative of her daughter’s sexuality and her ability to articulate it. The act of looking is not voyeuristic; rather, it is tempered by tenderness and wisdom.

Each story in the collection has a personality of its own. Despite the phenomenal range and variety of the plots, you find yourself relating to and remembering the context of each narrative. Moreover, there is a dexterous quality to the language, a stylistic flexibility. Deshpande juggles different techniques of narration, from first-person to third, and each voice is unique so there is no room for repetition or monotony. This is a commendable feat considering what are, in this reviewer’s opinion, the limitations of the vocabulary of the English language, particularly when it comes to describing either sex

or intimacy.

…While it is acceptable for men to brag about their sexual exploits, it is still taboo for women writers. The few women who do, usually hesitate to sign their real names to their writing. Writers who so much as hint at being sexually experienced – such as Meena Kandasamy, who openly writes about the experience of being Dalit and a woman, and Mridula Garg – often have to bear the brunt of moral hypocrisy. Writing erotica comes at the price of one’s reputation. Ruchir Joshi’s introduction to Electric Feather is testimony. Joshi explains the difficulty he experienced in soliciting stories. ‘One senior Indian writer, who writes brilliant erotics, disdained to even answer my email. Three others did variations of sputtering into their beer, “Me write porn for you!?! No fucking way!” and promptly crossed their legs, all three. One star of the firmament smiled very sweetly and said, “If I find the time, I’ll certainly think about it.”’

Deshpande is possibly the first contemporary Indian author in English to publish a collection of stories devoted entirely to the erotic…

~ Roselyn D’Mello is a journalist and writer in Delhi.

Other reviews

http://helterskelter.in/2011/08/book-review-slither/

http://www.businessworld.in/businessworld/content/Passion-And-Repression.html

http://www.himalmag.com/component/content/article/4633-spanking-words.html

and on this site,

Jai Arjun Singh’s review, among others.