Jai Arjun Singh – I would have been happy for even a bad review from him. I have been reading his reviews for a long time, so it makes me very pleased that he even read Slither, let alone that he actually enjoyed some of it!

Link to his own blog Jabberwock (lots of gyre and gimble there!)

and here’s the whole review:

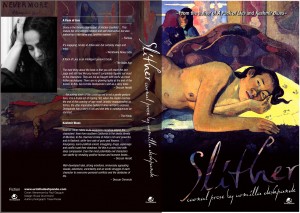

Spirit and flesh: on Urmilla Deshpande’s carnal prose

[Did a version of this for the Sunday Guardian]

It’s often said that Indian authors aren’t good at writing about sex – that they get self-conscious, or struggle to find the balance between biological descriptiveness and subtle, feather-touch erotica. Actually, the existence of the international Bad Sex Award – which has been thrown at such notable writers as John Updike, Norman Mailer and Tom Wolfe – suggests that awkward sex writing is a universal phenomenon. (The sole Indian winner of the prize so far is Aniruddha Bahal’s Bunker 13, with its analogies involving Bugattis and Volkswagens: “She is topping up your engine oil for the cross-country coming up. Your RPM is hitting a new high.”) But I admit that my initial reaction on coming across Urmilla Deshpande’s Slither was to be impressed that an Indian writer has even attempted a collection of “carnal prose” (as the subtitle puts it).

Once I began reading the book, I was pleased to find that not only is much of the sex writing here quite good, but also that the stories show imagination and variety. Sexual passion, in its many forms, plays a central role throughout, but these are also searching narratives about other aspects of the human experience: loss, insecurity, nostalgia, generational and cultural gaps.

One of Deshpande’s strengths is that she can bring a strong – and unexpected – charge even to seemingly mundane incidents, such as a woman and her mother-in-law chatting with each other while being measured for blouses by an old, half-blind family tailor. Or the same mother-in-law matter-of-factly saying that her aged husband acquires a temporary libido once a year, “usually after a wedding, when he has seen all you girls and your raw-mango breasts, and imagined everything that is going on in the nuptial bed”.

Like many short-story collections, Slither has its hits and misses, but the high points are very strong. In one of the best pieces, “Isis”, a young writer becomes infatuated with a long-retired movie siren; as his loins are stirred by a woman old enough to be his grandmother (and by talk of the effect she used to have on men in her heyday), we are reminded that sexual desire is as much a matter of imagination as of naked flesh. At the same time, other stories provide counterpoints to Isis’s feral, age-defying sexuality. Suman, the protagonist of “Slight Return”, is barely forty but she has never really had a sexual life at all – even her visits to her (male) gynecologist, she reflects, were warmer and more fulfilling than her emotionless trysts with her husband. When she accidentally sees her 16-year-old daughter making love with a boyfriend, she thinks about her own life and the many taboos she grew up with. But she has also accumulated life experiences that allow her to be accepting of her daughter’s sexuality: having done social work with rape victims-turned-prostitutes, she knows about women who never even had a choice in these matters. I thought the contrast between Suman’s wisdom and her private sense of desolation and discomfort was very well expressed.

The stories that didn’t work for me are the ones – like the stream-of-consciousness narrative “dUI” – where the prose becomes overly turgid and self-indulgent. (“What purpose has coincidence? To dam two streams into a single flow, to stroke an eager cock, suck a succulent nipple, arch the long back of a long torso in the moment of the end of the scene?”) But it feels churlish to criticise a writer for taking risks or for reaching beyond the confines of straightforward  narrative storytelling, and I admired at least the intent and ambition behind some of the more experimental pieces such as “Goblin Market”, which is a revisiting of Christina Rosetti’s controversial, symbolism-laden 19th century poem. (Writing this story appears to have been a form of catharsis for Deshpande, who says she was haunted by Rosetti’s work for years.)

narrative storytelling, and I admired at least the intent and ambition behind some of the more experimental pieces such as “Goblin Market”, which is a revisiting of Christina Rosetti’s controversial, symbolism-laden 19th century poem. (Writing this story appears to have been a form of catharsis for Deshpande, who says she was haunted by Rosetti’s work for years.)

narrative storytelling, and I admired at least the intent and ambition behind some of the more experimental pieces such as “Goblin Market”, which is a revisiting of Christina Rosetti’s controversial, symbolism-laden 19th century poem. (Writing this story appears to have been a form of catharsis for Deshpande, who says she was haunted by Rosetti’s work for years.)

narrative storytelling, and I admired at least the intent and ambition behind some of the more experimental pieces such as “Goblin Market”, which is a revisiting of Christina Rosetti’s controversial, symbolism-laden 19th century poem. (Writing this story appears to have been a form of catharsis for Deshpande, who says she was haunted by Rosetti’s work for years.)I was also amused by Deshpande mentioning, in her acknowledgements, that much of this book was written in a decidedly unsexy setting – during a family Christmas in Canada. “I often found myself in a roomful of nieces and nephews and in-laws and sisters, typing carnal prose into my laptop while eating and drinking whatever was handed to me … tea or coffee, turkey-and-cranberry sauce, bhel, chicken curry.” It reminded me of the caricature of the phone-sex worker who is really a slovenly, middle-aged housewife in a low-rent apartment, going about her daily chores even as her husky voice inflames her callers’ imaginations. As they say, it’s mostly between the ears.