http://www.timeoutmumbai.net/books/book_review_details.asp?code=495

http://www.timeoutmumbai.net/books/book_review_details.asp?code=495

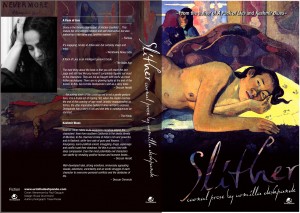

Carnal prose. Those two words on the cover of Urmilla Deshpande’s Slither may draw you to pick up the book. But a few paragraphs into this collection of short stories, you realise that there is much more to the book than erotica. Deshpande could well lay claim to a genre of her own – carnal noir.

The stories go beyond the sexual. Some are dark and mysterious in their thoughts, others are warped in their actions. Those expecting amorous reading may be a tad disappointed but those who persevere will be richly rewarded with the complexity of each story. The copulatory imagery is just a garnish on the prose that delves deep into the human psyche. The layers peel to reveal to the reader what each protagonist feels: shame, anger, jealousy, even confusion as their bodies seek out ways to satiate sexual urges.

The piece titled “dUI” is an excellent play on a coincidence that leads a man and woman to a place of “gentle blood and gentle love”, while “Isis” explores an inherited lust where a young man salivates over a has-been porn star only to discover her best co-star was his grandfather. In “Beyond the Pale”, an albino looks for colour in her life. She finds it only when she draws blood from her husband. You feel strangely sympathetic and see her as a victim and killer.

French impressionist Paul Gauguin’s 1897 masterpiece Nevermore O Tahiti, of a nude basking in seemingly post-coital glow is the front cover, setting the mood for the raw emotions that copulate with the strange circumstances within the collection. You want to know what the protagonists of each story did and why they did when they did. The author is not voyeuristic and her writing balances eroticism with sensitivity. Urmilla Deshpande’s prose seduces the reader’s mind. Karuna John

http://www.deccanchronicle.com/channels/lifestyle/books/slither-sex-menu-177

How many authors of Indian origin would gladly choose the subject? And a book of short stories it is, too. Having attempted to write romantic scenes in fiction, and knowing how tough it is to describe the details of an embrace, let alone osculation or for that matter sex, I knew that Slither: Carnal Prose by Urmilla Deshpande either had to be hugely wonderful or poetic smut.

Poetic because Indians excel in what I call the Wannabe Rabindranath Tagore-style essay writing — descriptive, rhythmical but still a load of convoluted balderdash. And smut because the protagonist and the man she is attracted to are watching a pair of snakes in a “loveknot”, “wrapped around each other, an elaborate motion of sinew and sex… time meant nothing, not to them, not to me…”

I groaned when I read this on the very second page.

How does she know what the snakes are feeling, if at all? Will one have to endure more voyeuristic scenes? Will they get better or just put you off sex for a while?

Yes, there are more instances throughout the book. Suman watched Biren “put his hands on her naked bottom, one on each side”, the ‘her’ here being Suman’s daughter. Suman is watching her daughter “making little sounds like a kitten, and still giggling”.

Oh spare me the bad marriage debate which stops Suman from reacting. If she stays to watch her school-going daughter make love to her boyfriend, and in graphic detail, it teeters on that precarious line that could be called smut.

The language of the stories — if you wish to call these episodes of sexual writing that — is so flowery and repetitive, you feel compelled to put down the book more than once. In fact, the words are cloying and claustrophobic so you don’t realise that there is not much of a story in it. Much like pornography that masks its explicit content by attempting to weave a story in the whole shebang. What was amusing to note is that the tone of voice in every story is the same, and I found myself saying, “what the hell?”

upon discovering that the protagonist is a man. The imagery or the sexual metaphor is a joke because it doesn’t really grow beyond “bananas” and “shaft”. Yes, it is a bold move indeed to choose to write carnal prose, but if the language of these stories is a cure for insomnia, and the characters do not evoke an iota of empathy, then the experimentation is a failure.

As a fan-girl of Jack Murnighan, who dissects and offers infinitely sane advice to writers on all matters of sex, I can safely say that writing in Slither does not turn you on. It is just writing about sex, woven in almost Victorian floral patterns that rely on breathy repetitiveness.

Instead of lying back and letting imagination run riot when you read the stories, you lie down and promptly fall asleep. This are very tedious tales of sex wrapped in old fashioned lace ripped off your granny’s bloomers, and just as passionless. And yes, the five marks for attempting carnal prose, stay.

Manisha Lakhe is the author of The Betelnut Killers