A friend sent us this link. The text is here, but can be seen in the Sparrow Newsletter Number 14. (Thank you Imran)

http://sparrowonline.org/newsletter.htm

In Marathi or in English, in person or in print, the prolific poet, fiction-writer, and translator Gauri Deshpande (1942-2003)has a distinctive voice: strongly feminist, wryly humorous—usually at her own expense, confident yet self-critical, irreverent yet steeped in tradition, cosmopolitan yet grounded in her love for language and place. No matter who or where her audience is, she is bound to challenge their assumptions, producing both discomfort and delight.

In 1993, as a postgraduate student preparing with trepidation for our first meeting at the University of Poona’s English Department, where she was teaching postgraduate courses, I carefully donned a traditional Pune sari to meet the daughter of the illustrious anthropologist Iravati Karve and the granddaughter of the illustrious social reformer D.K. Karve. To my embarrassed surprise, a tall, lanky, imperious-looking woman dressed in torn trousers came striding toward me and grasped my hand in a firm handshake. We became friends quickly, thanks to her openness and generosity, and my husband, son, and I have fond memories of our visits to her house during our stay in Pune, as we all ate and talked non-stop, and played fast and furiously competitive card games (the game of “Running Demons” I shall forever associate with Gauri Deshpande) with her and her daughters, son-in-law, and grandsons. Back in the United States a decade later when I heard the sad news of her untimely death, I could hardly imagine returning to Pune without her there.

While Gauri Deshpande was unquestionably one of the most important and innovative writers in contemporary Marathi literature, and was well-known and respected throughout India and among scholars of Maharashtra, she began her career writing well-received poetry in English. She published three collections with the Calcutta Writers Workshop and edited a collection of Indian poetry in English in the late sixties and early seventies, but then switched over to writing fiction in Marathi and made her name with her novellas and her translations. At the time of her death in 2003 she was relatively unknown beyond India; however, that was changing, since her work in English had been gaining greater exposure throughout the 1990s. One of her Marathi stories was translated into English and anthologized in the important two-volume Women Writing in India published in 1993, and her first collection of short stories in English, The Lackadaisical Sweeper, was published in 1997. Several of her important Marathi-English translations were also published or re-issued in the late 1980s and 1990s, including Sumitra Bhave’s Pan on Fire: Eight Dalit Women Tell their Story (1988), Jayawant Dalvi’s searing social critique, Chakra: a novel (1974, 1993), and Sunita Deshpande’s …and Pine for What is Not (1995), a controversial memoir by the wife and secretary of the popular Marathi playwright P.L. Deshpande.

Like Gauri Deshpande herself, her stories confound readerly expectations—whether the readers are Indians or non-Indians— of Indian society, and specifically of women, and the stories are often profoundly unsettling, jarring the reader out of complacency. In addition, they continually shift perspective, from India to the United States and back, from gender to caste-class, from mother to daughter, from the rational to the emotional, from the abstractly philosophical to the earthily physical, and back again. Further, the categories themselves are unsettled, as women resist femininity, Indians refuse to behave in a stereotypically “Indian” manner, and the direction of global flows are reversed, as Americans migrate to India and become entirely assimilated.

In That’s the Way It Is (Ahe he ase ahe), the story published in Women Writing in India, the utterly rationalist first-person narrator gains a new perspective on herself at middle age, in a chance meeting with an old friend, an American long-settled in India. As she goes literally and figuratively to buy glasses to correct her far-sightedness, she discovers that she has understood nothing at all of life and love. When her friend observes, “You really do need glasses to see up close” (475), his comment prompts a shift in perspective, as the narrator, remembering so many incidents in the past, realizes that he has loved her silently ever since their childhood, while she has remained oblivious. “And suddenly, I saw…I was all wrong; I had missed my way in life. My constant arrogant insistence— “What I say is right!”— had kept me from knowing what is was that others understood about life. I didn’t let myself know. All this”. This capacity to be at once opinionated and self-critical is typical of Gauri Deshpande’s writing.

In the title story of The Lackadaisical Sweeper, two newlywed upper-middle-class wives, one Indian, the other American, stationed in Hong Kong with their businessman-husbands, meet and become friends as they take their daily morning walks. At first the American woman appears to be stereotypically brash and self-involved, the young Indian woman (aptly named Seeta) equally stereotypically meek and submissive. However, the Indian wife’s unquestioning submissiveness to her husband’s demands leads her to betray her American friend’s open confidences about her husband’s business dealings. Learning from Seeta that her American friend and her husband are Jewish, Seeta’s businessman-husband is able to use anti-Semitism and his wife’s inside information to force the couple to flee the country, grabbing their real-estate holdings just as the property market is booming. The reader’s disgust shifts from the uninhibited sex talk of the American woman to the unethical behaviour of the Indian woman. And then, in a characteristic shift, Gauri Deshpande gives a silent, sullen street sweeper the last word. Every morning the American woman has greeted him as they pass him on their morning walks, trying in vain to elicit a response from him. In the closing scene, Seeta greets him and he answers back, to her delight, though she understands nothing of what he has said. In her parting shot, Deshpande leaves us with a view from below: “It was fortunate that she did not know Cantonese”. Wealthy, sheltered Seeta’s naiveté does not excuse her from complicity with her husband’s land-grab plot, neither does it excuse her total ignorance of the sweeper’s point of view. The reader is left pondering the sweeper’s judgment of Seeta, who may be a virtuous Indian wife, but is not a good human being.

In Map, a tribute to Edward Said, a middle-aged woman reclaims her body as her own territory after a love affair has ended. The story draws upon the postcolonial critique of colonial thought as a gendered discourse that designates the colonised as female, a blank canvas passively desiring to be conquered and mapped. Her ex-lover was the colonial explorer cartographer, drawing the map of her body in his own, exoticised terms. As in Edward Said’s Orientalism, where the “Orient” as represented by the European Orientalism bears no resemblance to actuality, but is a projection, a “will-to-power”, of Europe itself, in Deshpande’s story,the female first-person narrator now recognises “that the me in his mind had nothing to do with the me in my mind”. Taking pleasure in self-discovery at last, she declares, “it’s my body now and my map”.

In my view, Gauri Deshpande’s refreshing frankness in discussing the female body and female sexuality is never offensive, because patriarchal representations of women use a language of power and domination, while hers use a language of love and self-acceptance.

In Insy Winsy Spider, another story in the same collection (translated from the Marathi original Bhijata Bhijata Koli, a mother is forced to recognise her daughter’s difference from herself. The mother is a highly-educated professor of Buddhist philosophy, as scholar of the Self who ironically seems to have little self-knowledge. She and her husband, also a philosophy professor who have named their daughter Maitreyi, “to help her on her way to greatness,” are mortified when the daughter announces that she has no interest in studies and is going to get married, without even having done her BA. The next day, as the mother clears her mind to write an academic paper on the development of self-awareness in the ‘self’, the sight of her daughter chopping onions gives her a sudden revelation: while all growing children must learn to differentiate the ‘I’ from the ‘not-I’, she, in her self-involvement, has failed to differentiate herself from her daughter, despite her age and education. Like the spider in the nursery rhyme, climbing back up the water spout, “It was necessary to begin all over again…‘I’ am not this Maitreyi”.

I want to close with a few personal reminiscences of Gauri Deshpande that might shed some light on how her mind worked. With regard to the title of the story, Insy Winsy Spider, she once told me that one of her professors during her postgraduate studies in English literature insisted that his Indian students read English nursery rhymes in order to become as fully immersed in the language as a native speaker. She herself was in complete command of English, confident enough to reshape it in her own image. With regard to her firm commitment to write in Marathi, she once observed with a wry smile how much more money she could be making if she were writing in English. With regard to her exalted caste status and eminent parentage, although she rejected many upper-caste/class social and gender norms, Deshpande loved the language and culture of her community. Talking to fellow-Marathi writer Ambika Sirkar, she once observed sadly that, with the passing of their generation, certain turns of phrase particular to their community would disappear forever. When we visited her in Pune, even as she offered her guests a cold glass of beer, she also offered us a tumblerful of a cooling green mango drink explaining that it had to be drunk at this particular time of year.

As Shanta Gokhale wrote soon after her death, “How could this strapping, handsome, vibrant, gutsy, intense and intellectually passionate woman have just ceased to exist? Gauri had an insatiable zest for living, for experiencing new places and people, for friendship, for loving and giving” (Woman of Substance). As a writer and as a person, Gauri Deshpande has left a gap in English and Marathi fiction and society that is not easily filled.

— Josna Rege

Associate Professor, Department of Languages and Literature, Worcester State College, Worcester, MA, U.S.A.

My Marathi is good enough to talk to my sister (whose Marathi is worse than mine), and not at all good enough to read the translation.

My Marathi is good enough to talk to my sister (whose Marathi is worse than mine), and not at all good enough to read the translation.

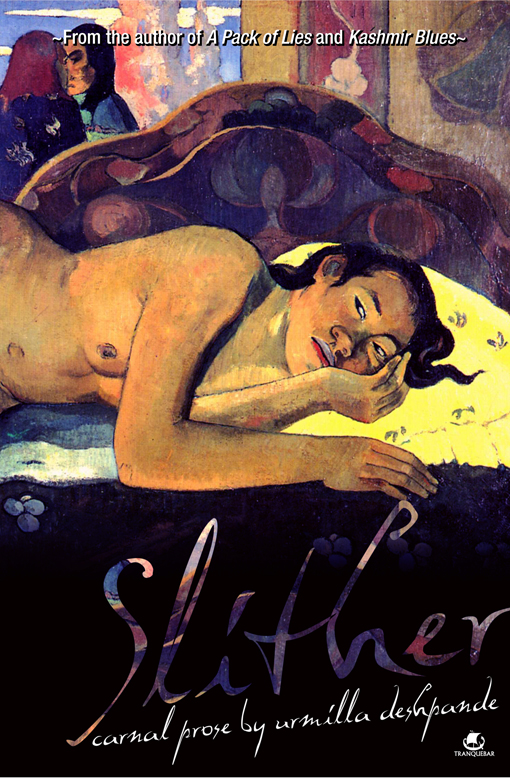

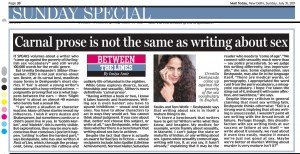

Mail Today, New Delhi, Sunday, July 31, 2011: Between the Lines by Insiya Amir

Mail Today, New Delhi, Sunday, July 31, 2011: Between the Lines by Insiya Amir http://www.timeoutmumbai.net/books/book_review_details.asp?code=495

http://www.timeoutmumbai.net/books/book_review_details.asp?code=495